“One of the first essentials for any adult who wishes to help small children is to learn to respect the different rhythm of their lives instead of trying to speed it up, in the vain hope of making it synchronize with ours.”

(Standing, 2008).

I’d the start of a new school year! With the beginning of every new year comeds the resetting of routines, and renewed hopes for effectiveness and cooperation from everyone. At home: making lunch the night before, new bedtimes, dinner on the table by 6:00 p.m., everyone dressed and out the door by 7:30 a.m. At school: daily clean-up jobs done before pick-up time, the morning work-cycle started by 8:30 a.m., lunch done by 12:15 p.m. so the children can get outside by 12:30 p.m., and daily check-ins with students. In a few weeks, some of these routines will start to soften. A few weeks later, the adults will become frustrated and discouraged, and the children will push back against the routines, which often leads to adults giving in and loosening up even more, or pushing back and “taking control”. Either dynamic invites misbehavior in the children, and more discouragement all around. It’s stressful for everyone!

Let routines be the boss! When routines are well established, they become a form of communication. With consistent routines, children can predict what is coming next. They are able to develop autonomy and independence because they are not dependent on adults to tell them what’s coming next. Predictability supports self-regulation. When children know what to expect, they can prepare themselves, emotionally and practically. They develop their will freely within pre-established limits.

Without consistent routines, adults must become the boss, because children depend on them to know how to prepare for an upcoming event. This puts the agency in the adults’ hands, and can invite power struggles, passivity, or anxiety in children and adolescents (adolescents are especially prone to power struggles if the adult is the boss) when cooperation and teamwork are needed.

A few years ago, I was asked to observe an elementary teacher. She was having difficulty with the lunch transitions. There was a lot of misbehavior from the children, and the teacher felt the environment was becoming unsafe. After observing lunch for a few days, it became clear what was inviting the misbehavior. Each day both the transition and the preparation for the transition looked different. One day, the class skipped their morning cleanup routine and went right to lunch, so that the teacher could finish a lesson. The next day, lunch started 15 minutes late, and the children needed to eat quickly before going outside. On the third day, the class followed the routine that was set up at the beginning of the year, but the teacher had to do a lot of directing and reminding. As she directed and reminded, the assistant teacher became more passive. Some children followed the teacher’s directions, and others did not.

What happened? In this case, the adults were overriding the routines, depending on the perceived needs of the moment to dictate what the transition would look like. Of course, from time to time this can happen because every day isn’t perfect. However, in this situation, the routines were consistently inconsistent, so the children never knew what to expect. As a matter of fact, the assistant teacher also didn’t know what to expect. Both the students and the assistant became dependent on direction from the lead teacher. This lack of consistency invited power struggles in the children and passivity in the other adult, because the teacher was the boss.

After reviewing the observations, the teacher and her assistant did some detailed transition planning together, and created a routine for themselves that would help them support each other in maintaining the consistency of the routines. They also brought up the issue in the Class Meeting. The teacher shared her concern about the misbehavior and acknowledged her role in disrupting the routines, which left her students unsure of what to expect each day. The class brainstormed several ideas to help keep the routines consistent, including choosing a timekeeper for lessons, and how to clean up more quickly and effectively at the end of the morning work cycle. Within a week the lunch transitions looked completely different. The assistant started taking on more leadership, naturally; there were far fewer power struggles, and the students even started redirecting each other when things got off track. The children and assistant were empowered because routines were, once again, the boss.

While this example took place at school, the same dynamic can take place at home! So, how do we let routines be the boss? Here are some suggestions for creating successful routines to help children develop independence, cooperation, responsibility, and problem-solving skills:

The preparation of the adult.

When adults are truly present during routines and transitions, children feel secure. To be present for routines, takes intentionality and preparation. Be sure to take time to plan how you will prepare for routines and transitions so that you can be fully present. This often means taking time to follow a routine (cleaning up a lesson, grabbing a cup of coffee, getting your shoes on, etc.) before the children.

Involve children and adolescents in discussing and creating routines for the class or family. When people (of any age) are involved in solving problems, they are more likely to cooperate when it’s time to cooperate and help follow-through because they are invested in the process. They helped create it!

Critical thinking and problem-solving skills are learned through experience. When children are involved in the planning of routines, they get a chance to think about, discuss and experience why a routine might work or not. They will also learn to work collaboratively, which is a critical social and life skill! Finally, when children are involved in the creation of routines, there’s a higher probability that your class or family will come up with routines that work well, because the problem solving will be done, taking into consideration multiple perspectives and ideas.

Plan for changing circumstances with children. Let’s face it, life happens, and circumstances can change from one day or one week to the next (especially in the home). However, many circumstantial changes are predictable. When setting up routines, take make a list of predictable schedule changes. At home, these predictable changes might be: business trips, after-school activities, date-nights, etc. At school, they might be: three-day weekends, field trips, fire drills, snow days, etc.

After making a list of predictable schedule changes, talk about alternative plans. These are simple adjustments to your regular routine plans. At the class or family meeting, if a alternate plans need to be made for a schedule change, make a plan together so everyone knows what to expect.

Review routines in family and class meetings. Sometimes our best-laid plans don’t work the way we had hoped. A routine might not be working. Why? Maybe the routine was too ambitious and there isn’t enough time to accomplish everything in the allotted time. Maybe the order of the routine isn’t working. Or the children need more help than was anticipated. When this happens, it’s tempting for adults to throw in the towel and take over.

Take time to review how routines are working, in your family or class meeting. “How is the morning routine working for everyone?” If adjustments need to be made, problem-solve together. Mistakes are an opportunity to learn. As well, this process helps maintain an environment of cooperation and mutual respect. If things are going well, reviewing the routines will affirm the success of your family or class teamwork.

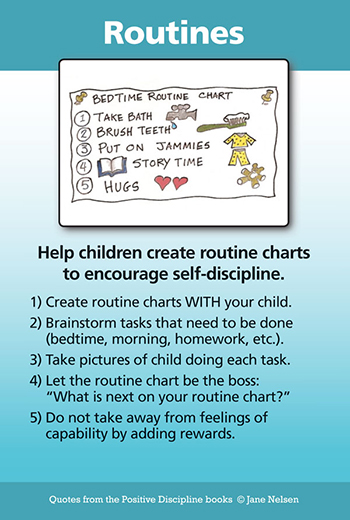

Create routine charts. Routine charts work especially well for young children, although people of all ages find them helpful. Routine charts give visual cues to what’s happening next. Parents and teachers can follow-through by simply pointing at the chart and asking, “What’s next on our routine chart?” Older children can create their own and check off the steps of their routine as they accomplish them.

Follow-Through. When children are involved in creating routines, problem-solving, and reviewing routines, they develop a healthy sense of independence, and they are more willing to cooperate when the adult needs to follow-through. Creating routines with children doesn’t mean that children or adolescents will always follow the routines. As a matter of fact, most will have times when they do not follow the routine. Limits aren’t limits until they’re tested. Children want to know that adults will follow-through. This creates an environment of safety and predictability. If you have created routines with children, it will be easier to follow-through. When children don’t follow the routine, you can simply ask, “What’s next?”, or “What was our plan?” Then, stay present, warm and silent, allowing the child the dignity to cooperate using their own agency.

Until next time…

References

Maria Montessori Her Life And Work (hc). (2008). India: Cosmo Publications.