“We must give him the means and encourage him. ‘Courage, my dear, courage! You are a new man that must adapt to this new world. Go on triumphantly. I am here to help you.’ This kind of encouragement is instinctive in those who love children. ” (Montessori, 2012)

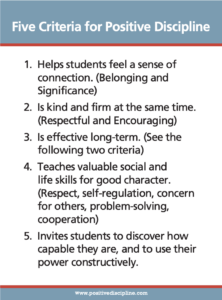

In his book, Children the Challenge, Rudolph Dreikurs devotes an entire chapter to the subject of encouragement. Dreikurs believed that “Encouragement is more important than any other aspect of child-raising. It is so important that the lack of it can be considered the basic cause for misbehavior.” (Dreikurs, 1991). What strikes me about this chapter of his book, is that nearly 2/3 of the chapter focuses on encouraging children through holding them accountable, in a supportive manner, for what the adult knows they are capable of and responsible for. The rest is devoted to verbal encouragement. Verbal encouragement is incredibly important, but it’s only one part of the encouragement puzzle.

Many of us have had experiences where someone encouraged us, not by words, but through their actions. Maybe they didn’t let us “get away with” doing something halfway. They held us accountable to what we were capable of. They seemed to believe in us, even if we didn’t believe in ourselves. When we look back at those experiences, how did it affect us? How did it affect how we felt about ourselves, and our sense of our own capability?

When I was in 6th grade, I had one of those teachers, Mrs. P. She believed in me, and she’s one of the reasons that I became a teacher myself. Before entering her class, I had experienced little success in school, behaviorally and academically. My attitude towards school was negative to put it succinctly. I had two favorite times of the school day: recess and dismissal.

The first thing that was different about Mrs. P. was that she took time to get to know me both as a student and as a person. She treated the children in the classroom with kindness and respect. She took time out of her day to spend with me when I struggled with something we were learning. Along with her kindness and investment of time, she also treated me as capable. While I cannot recall one conversation that we had, or one encouraging word that she gave me (although I’m sure there were many), I do remember that she expressed a strong belief in what I could do. She challenged me, held me accountable for what she believed I could do, and she was firm about it. Behind that firmness she communicated a sense of trust in me, that I was more capable than I thought I was. She was right.

Let me share with you the rest of this story. If you had asked me just a year ago what the impact of being in Mrs. P’s class was, I would have told you that I was an A and B student for the first time, and that she helped change the trajectory of my career as a student. However, only one of those two statements is true. Last year, my family moved from Maine to Ohio. As one does when moving, I started going through mementos from my childhood, including a box of report cards that my parents had saved. In that box was a report card from Mrs. P’s class. I read it and was shocked. Apparently, I was a solid C student in her class, just like I had been before she was my teacher. I couldn’t help but laugh.

Alfred Adler famously said, “We are not determined by our experiences, but the meaning we give them is self-determining.” We become what we believe, and encouragement has the power to influence our beliefs. My relationship with Mrs. P changed how I saw myself. She was kind and firm, had held me to high expectations. As a result, my grades gradually improved over the years. I actually became an A and B student in high school. The B’s dissipated over time, and I graduated college with highest honors, third I in my class out of 1200. Thank you, Mrs. P.

Research has shown that when students have positive self-perceptions to be successful and resilient in school. (Grumen, 2016). And there is a strong correlation between teacher expectations and students’ self-perceptions. In one study, even when a teacher’s expectations were not well aligned with a students’ actual abilities, those students whose teachers had higher expectations of them showed higher academic achievement, and those students whose teachers had lower expectations showed lower achievement. (Gentrup, 2020). Children do better when we show faith in them! This doesn’t mean that we should arbitrarily place high expectations on children. It does caution us though to make sure our expecations aren’t too low, either. We are called as Montessorians to carefully observe children and introduce them to materials that are aligned with their abilities in order foster the experience of success. Our expectations should be based on observation and trust in children’s capabilities.

Children are constantly making decisions about who they are, and how they will navigate the world around them. These decisions form beliefs. These decisions and beliefs are influenced by their environment. We cannot lecture, reason or talk a child into believing they are capable. They need to experience it. Words help, but our real power lies in creating an encouraging environment where children discover their own capability.

Let’s take a look at how to prepare an environment where children can discover how capable they really are. These suggestions apply to both the social-emotional and academic environment:

Taking time for Teaching

This is something we do well in Montessori classrooms. All children have different tolerances for taking risks. Some children seem to just naturally be willing to try something new or to solve a problem they have never experienced. Taking time to teach tasks or skills, step-by-step, will meet the needs of all children, no matter how they approach something new.

Younger children, ages 3-6 need definite and concrete steps when learning something new. Sometimes adults will confuse younger children by giving too many options in how to approach a task or skill. They are trying to be respectful and flexible, but younger children are still developing reason and learn from their experiences. So, so don’t be afraid to choose a very specific way to teach them the task or skill, and then let them experiment with different methods as they become capable in following your directions. Taking the time to teach, helps children understand how to do something clearly, and helps adults better understand what they can expect from the child. This is critical in setting appropriate expectations.

As children become more capable with a task or skill that has been taught to them, be sure to step back and let them do it themselves. When it’s time to take a step back, be sure to give the risk taker some more room to experiment and learn through his own experience and mistakes. With children who are less likely to take risks, take small steps back, but be sure to step back!

Set high and achievable expectations. Have faith in children!

Did you ever have a teacher, parent or boss that held you responsible for what they knew you could do, even if you didn’t think you could do it? How did you feel? How did you respond? Through careful observation of our students, we discover how capable they are. With this understanding, an adult can express belief in a child or adolescent, with a confidence and certainty that the child may not possess in herself yet. This confidence can be contagious. When children realize that your confidence in their abilities was warranted, a trust develops, not only in your belief in them, but in their belief in themselves.

Provide challenge.

Most children love a challenge that they can conquer with hard work. Too often we over or underestimate or overestimate a student’s abilities, whether it be academically or socially. Both estimations can be discouraging. Underestimating can cause a child to perceive that you don’t have confidence in their abilities, and possibly that they need to be protected. Overestimating can cause a child to perceive that she’s inadequate, or unable. Observing and connecting with our students helps us to maintain appropriate challenge so that students develop confidence and sense of capability.

Involve students in problem solving.

When students are involved in the problem-solving process, especially when the problems involve them, they feel trusted, respected, and significant. Wherever possible, seek to involve children in mutual problem solving (Class Meeting, Four Steps for Follow-Through, Conflict Resolution). When people feel trusted, they are encouraged. When they are encouraged, they do better.

Give students meaningful responsibility.

Students love to help, but even the youngest children pick up on an inauthentic request for help. Be sure to look for opportunities where children can make meaningful contributions, feel trusted and discover how capable they are. Are there tasks in the classroom that you do that you do that a student could do? Are there opportunities for leadership that children could take on that would help build their confidence and make a real contribution? Be sure to avoid giving responsibilities that are not truly meaningful to the classroom community. For example, adding “filler jobs” to the classroom job chart so everyone has a job (even if it’s not meaningful). Children pick up on this, and this can lead them to see all classroom responsibilities as unimportant, and more importantly their role in fulfilling those responsibilities as unimportant. Children are hard-wired to contribute to others, and through their authentic contribution they develop a sense of significance.

Allow students to struggle and make mistakes.

Allow children to make mistakes communicates that you have confidence in them and their abilities to overcome obstacles. One of the best ways to do this is by doing nothing. A simple smile or a statement like, “I trust you’ll figure that out,” is all that’s needed when a student makes a mistake that you know they can correct. This approach is so important today, when many parents are afraid to allow their children to experience discomfort, disappointment or failure. Natural consequences allow children to experience the effects of their mistakes so they can learn from them, naturally. It is impossible to build resilience or an attitude of “I can figure this out.” if you aren’t given the opportunity to struggle, to make mistakes and to learn from those mistakes. The rule of thumb when allowing children to learn from their experiences, is to make sure they have the tools, offer encouragement, and trust in their capabilities!

Let go of the product and focus on the process:

This one may seem self-evident to Montessori teachers, but I think we can all admit that sometimes we fall into the temptation of instilling our agenda under the guise of doing what’s best for the child. For instance, have you ever moved a child onto a material too soon because you wanted them to get to a certain place, academically, before the end of the year? Many of us have done this, and the results are almost always the same – the child experiences discouragement.

The same principle can apply to a child’s behavior. Sometimes we want children to learn what we want them to learn from a situation, and instead of listening, and allowing them to make their own mistakes, we insert ourselves, giving lectures and trying to help children understand a different point of view. We’re focused on the product rather than supporting the process for the child. Trust the process, trust the child! “I trust that you can figure this out.”

Until next time…

References

- Dreikurs, R., Stolz, V. (1991). Children: the challenge: The classic work on improving parent-child relations-intelligent, humane, and eminently practical. United States: Penguin Publishing Group.

- Montessori, M. (2012). The 1946 London lectures. Montessori-Pierson Publishing Company.

- Gentrup, S., Lorenz, G., Kristen, C., & Kogan, I. (2020). Self-fulfilling prophecies in the classroom: Teacher expectations, teacher feedback and student achievement. Learning and Instruction, 66, 101296.

- Gruman, J. A., Schneider, F. W., & Coutts, L. M. (Eds.). (2016). Applied social psychology: Understanding and addressing social and practical problems. SAGE Publications, Incorporated.