Learning to communicate with others is a lifetime process. Communication difficulties confound adults, and lead to misunderstanding, resentment, conflict and discouragement. But this doesn’t have to be the case. Students in a Montessori classroom are given the gift that so many of us who teach Montessori were not given: an environment where open communication, understanding, and real problem-solving can take place. By teaching our students to communicate respectfully and effectively, we give them an opportunity to build strong healthy relationships and develop lifelong social skills that will support them in every area of their life. It’s important work!

Most Montessori classrooms teach children to resolve conflict with one another. It is a critical element of the classroom, as children need to develop social independence as they develop their overall independence in the classroom. Before students learn to resolve conflict and solve problems within the classroom community, however, it’s imperative that they learn to communicate in a way that will promote understanding and problem-solving. Let’s look at the three components of developing respectful and effective communication skills: speaking, listening and non-verbal communication.

I Language (ages 5 through Adolescence)

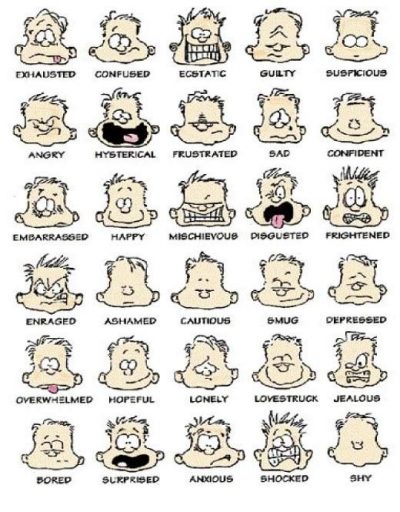

Everyone wants to be heard. But, too often students speak to one another in ways that encourage the listener to tune-out or shut down. This creates more conflict when problem-solving is needed. Here are some of the ways that students communicate that create barriers to open and effective communication:

- Blaming

- Criticizing

- Arguing

- Fault-finding

- Lecturing

- Scolding

- Dismissing

- Teasing

- Directing

- Changing the subject

- Advising

- Exaggerating

- Denying

If you’ve facilitated conflict resolution with students, you know how quickly the process can break down when students begin to communicate in these ways. The children leave hurt and frustrated, and the teacher is also discouraged.

Using I Language gives children the tools that they need to express themselves in a way that is more likely to heard and received by the listener. Here is the model for I Language that we use in Positive Discipline (children 5 and older):

“I feel_______________, when ________________, and I wish ______________.”

I first learned about the concept of using “I” statements when I was a new teacher in a Lower Elementary class. I would teach the children how to say, “I feel____________ because ____________,” when they were solving a problem with another student, instead of just using blame statements, or “You” statements, like, “You called me a wimp, and I don’t like that.” This was a good start because it got the children to start focusing on how they felt rather than just finding fault with the other child involved.

However, What I found, was that the “I feel” statements weren’t really opening up communication as much as I hoped they would. There was still an element of blame and defensiveness that was permeating the conversations when children were resolving conflict. Here is what a typical conversation sounded like:

Amari: “I feel sad because you teased me about poem.”

Kayleigh: “Well, I feel sad because you always work with Abby, and always leave me out.”

Amari: “If you didn’t always tease people, maybe they would work with you…”

You get the point. Of course, I would need to be present and facilitate such a conversation so that it didn’t devolve to the point of more hurt feelings and tears. And, many times, just getting through the conflict resolution process without the problem becoming worse was the victory.

When I started using the format above (I feel______, when _______, I wish ______), I began to see a real transformation in the conversations between students when they sought to resolve conflict. The conversations were becoming two-sided, and the students were becoming more independent, needing less adult support and facilitation. The last portion of I Language was the key. When the speaker asked for what she wanted at the end of the I Language statements, the speaker took ownership of the problem. He asked for what they wanted, and that gave the receiver the trust and dignity to choose whether to resolve the problem that way, or to offer another idea. When the speaker just used an “I feel” statement, it implied that the receiver was responsible for the speaker’s feelings, and then to boot, gave the receiver no way to help or resolve the problem. It was as if the speaker was saying, “I feel sad because you teased me in front of the class. It’s your fault, now you figure out how to fix it.” This would back the receiver into a corner, with only two ways out: feel bad or defend herself. The latter option was most popular.

Take a moment, and put yourself into the world of a child or adolescent. Pretend for a moment that your friend had just approached you and asked you to resolve a conflict with him or her. Consider how might you feel, and what decisions might you be making, when your friend communicates their problem to you in each of the following ways:

Friend: “I felt angry and embarrassed when you yelled at me in front of all the other kids when we were waiting in line.”

Friend: “I felt angry and embarrassed when you yelled at me in front of all the other kids when we were waiting in line. I wish you would just talk to me privately if you are mad.”

How might you feel when receiving each of these statements from your friend? What decisions might you be making in response to each of those statements?

Another benefit to using I Language is that it gives students the ability to resolve minor conflicts more naturally in their day to day interactions. When I Language becomes a working part of the students’ communication skill set, they can use it more organically, and simply talk to someone briefly, rather than having to use the formal conflict resolution process/area. This helps keep the conflict resolution process/area as a special place or process to solve problems that need more support or structure (and lets the teacher get some lessons in)!

Bugs and Wishes (ages 2.5 to 5)

Identifying feelings requires some abstract processing and self-awareness that the younger children in a Children’s House classroom will not have developed. That is OK, they can still begin to learn respectful communication skills, ask for what they want, and begin to resolve conflict. The direct aim of conflict resolution in the Children’s House classroom is to learn to be assertive, respectfully, and to set clear and appropriate boundaries. Instead of using feeling language, young children can simply use the words, “It bugs me,” or another simple phrase that communicates that the child is angry or sad.

“It bugs me when you eat all the snack. I wish you would leave some for someone else.”

“I don’t like it when you called me ugly. I wish you would stop.”

“It hurt me when you pushed me on the slide. I wish you would keep your hands on your own body.”

Until next time…