She must fashion herself, she must learn how to observe, how to be calm, patient, and humble, how to restrain her own impulses, and how to carry out her eminently practical tasks with the required delicacy. She too has greater need of a gymnasium for her soul than of a book for her intellect. (Montessori, 2004)

A number of years ago I taught a class of twelve Lower Elementary students in a school room that was converted from an old farmhouse. Our school was new and growing, I was the head of school and the only teacher . This meant that during the school day sometimes I had to leave the classroom for a few minutes to do things like answer an important phone call, go to the restroom or sign for a package. Because of the many hats that I wore in the school the kids in my class learned to become independent, and to be helpful to one another. They were also regular children, children who misbehaved from time to time.

One day, I had to leave the classroom for a few minutes to use the restroom on the second floor of the farmhouse, where my office was. I was only gone for about 5 minutes when I heard a great disruption downstairs. I heard loud voices, furniture moving, and a lot of noise! I had been under a lot of stress with my workload, and my reserves were low. My first thoughts were, “Why can’t they keep it together for 5 minutes while I use the bathroom!”

I stomped down the stairs fully intending to give the third degree to whoever caused all the commotion. I still can’t tell you what made me to pause and take a deep breath before I entered the room. But I did. After collecting myself I entered the room. What I saw amazed me, humbled me and made my eyes well up with tears. Apparently, when I washed my hands in the sink, one of the pipes in the floor had broken, and water was pouring down through the ceiling into the first-floor classroom. The children had reacted quickly and had moved tables and shelves out of the way of the incoming water. They had also emptied trash cans to catch the waterfall coming from the ceiling. I couldn’t have done a more effective job myself. They saved about $500 worth of materials, as well as the rug beneath the leak.

Had I reacted to my emotional state as I stomped down the stairs, I would be recalling that moment today as one of my biggest regrets as a teacher. Now, with greater understanding of myself and how the brain and emotions work, I understand what happened that day when I paused before entering that room.

Here’s a great video by Daniel Segal that describes how the brain works in a moment of stress: https://youtu.be/f-m2YcdMdFw?si=5FAg0PnBnRHkBU5q

When we “flip our lid” our pre-frontal cortex, or “rational brain”, is closed for business. It is no longer the guiding force of our actions. We begin reacting from the mid-brain which governs our memories, fears, and “fight or flight” response. When the pre-frontal cortex is not engaged and we have little control over our reactions, and we make our biggest mistakes relationally: assuming, blaming, raising our voices, threatening, saying things we wish we could take back, etc. However, when we take the time, intentionally, to reintegrate the pre-frontal cortex, relational mistakes diminish, and real problem solving begins.

What happened in my experience above, with the broken pipe, was that I paused and took a few deep breaths, literally giving myself a moment to cool down (deep breathing brings oxygen to the brain and can speed up the process of reintegrating the prefrontal cortex). I immediately started to relax. This pause helped reintegrate the prefrontal cortex and gave me the ability to regulate my emotions, take in the information that I saw and respond flexibly and with understanding.

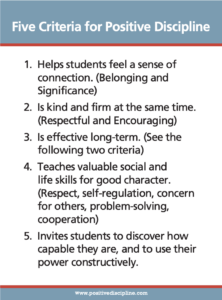

In case you haven’t noticed, children “flip their lids” too. In a Positive Discipline classroom, we help facilitate the process of reintegrating the brain, or cooling down, by creating a designated space for children to go when they are upset. We call this space a Positive Time-Out area. When children feel angry, hurt, overwhelmed or sad, they can choose to go to the Positive Time-Out area and stay until they have regained perspective and emotional control. Once they are feeling better, they emerge with the ability to connect with others and problem-solve. Positive Time-Out is a concrete tool to help children develop the critical life skills of self-awareness, self-regulation and problem-solving. (Note: We use the term Positive Time-Out to differentiate a cool down time from a punitive time-out. A punitive time-out is used by adults to punish a child for their misbehavior. It is recommended that the Positive Time-Out area be given a different name to reflect its purpose).

Who Should Take the Time Out?

Have you ever sent a child to time out when they misbehaved? If so, did it help solve the problem? Did the child’s behavior improve? I’ve done it, it didn’t help. As a matter of fact, it often led to a deterioration of my relationship with the child and the unwanted behavior continued or worsened. To quote Jane Nelsen, “Where did we ever get the crazy idea that in order to get children to do better, first we have to make them feel worse? Children do better when they feel better. Don’t we all?” (Nelsen, 2011).

The truth is that we adults often use a punitive time-out when we are the ones who need to cool down. But modeling a Positive Time-Out can be a powerful tool in supporting strong, mutually respectful relationships with children. This can be especially if followed by problem-solving with children. Here are some suggestions for teaching and modeling:

Discuss “Flipping Your Lid” – Explain to the children what happens in the brain when we “flip our lid”. Also explain how giving the brain time to cool down allows the pre-frontal cortex to re-engage so that our rational brains can begin to work. Both Daniel Siegel and Jane Nelsen have videos on YouTube to demonstrate this lesson. Children as young as 3 can understand this concept.

Model cooling down – If you find yourself losing your patience, or in a power struggle, let the children know that you need time to cool down so that you can solve the problem with them respectfully. Make sure you let them know that you will come back and work things out with them when you are ready. It takes two to engage in a power struggle! If you are using a Positive Time-Out area in your classroom children will understand that you need to cool down sometimes too!

Make amends when you make mistakes – Everyone makes mistakes. If we are able, as adults, to make mistakes and take responsibility for them our children will learn from us that it’s OK to make mistakes, and it’s safe to take responsibility and make amends. Making amends also offers your children the opportunity to decide to forgive! What an incredible life skill to learn when you are young.

Problem-solve with children – A common situation for adults to lose their patience is when a child engages in a repeat misbehavior that affects others. You might say to yourself, “I’ve talked to her a thousand times about putting her lunch away!” It’s tempting to impose a consequence when a child repeats a misbehavior. However, when we’re upset, the consequences that we impose are usually punitive, and this can invite rebellion, resentment or passivity. This often worsens the problem. Instead, work with the child to solve the problem at hand.

- Have a friendly and frank discussion about what’s going on for each of you regarding the problem.

- Discuss ideas to solve the problem, together.

- Choose an idea to try for a week. Be sure it works for both you and the student.

- If the child breaks the agreement, don’t engage in reminding or arguing. Simply follow through by saying, “We had an agreement,” remember to remain warm in this reminder don’t say it with a threatening tone.

Here’s a story shared with me:

Ben (age 9) had been teasing Robert, one of the younger students in the classroom. It seemed so intentional and cruel. I had been teased as a child at school, and I was really upset at his behavior. When I would confront him about it he would deny it, or say that the other student was doing it too. I started sending him to our peace [Positive Time-Out] area. I knew I shouldn’t be doing that because the children would begin to see it as a place of punishment, but I didn’t know what else to do. I was so angry with him. I reached out to friend for help. She suggested that the next time I got upset with Ben that I take the time-out before talking to him, after I had cooled down. Honestly, I felt a little embarrassed to be reminded of this. A few days later, I had the chance to practice what I teach. Ben was teasing one of the younger students. I got upset and started to give him a “stern lecture”. Mid-sentence I stopped and let him know that I was really angry and that I needed some time to calm down. He seemed honestly surprised. I came back about a half an hour later and asked to talk to him privately. I explained why I was upset and apologized to him for treating him disrespectfully. He seemed to really soften. I asked him if he would be willing to work on solving problem with me, and he agreed. In our discussion I found out that Ben had really struggled to read his first couple of years in the classroom. He said he felt stupid. He didn’t want to be the stupid one anymore. Ben decided that he would start to help Robert rather than tease him. And he did! I’m so grateful I got the nudge from a friend to control my behavior and not Ben’s!

Until next time…

References:

- Montessori, M. (2004). The discovery of the child.India: Aakar Books.

- Siegel, D. (2024, June 4). Hand Model of the Brain. Dan Siegel. https://drdansiegel.com/hand-model-

- Siegel, D. (2015, January 22). Brain Insights and Well-Being. Dr. Dan Siegel. https://drdansiegel.com/brain-insights-and-well-being-3/

- Nelsen, J. (2011). Positive Discipline: The Classic Guide to Helping Children Develop Self-Discipline, Responsibility, Cooperation, and Problem-Solving Skills. United Kingdom: Random House Publishing Group.